THE HEALING PROCESS

originally published in The Studio Potter magazine Volume 20 Number 1

(above: Small Black Eve, 1988. Approx. 17 in. tall. Photograph: Eric Shambroom)

I do not think there is a women’s spiritual movement at this moment in America, although something similar to it may be evolving. What is happening is the disaffection of many women from the traditional male-centered religions and the consequent search by some women for a new form of spiritual expression. From my experience and that of a number of women I have spoken to in depth about this, the quest seems to be highly individualized.

For many contemporary women, it has been useful and perhaps necessary to spend a period of time in intense exploration of a female-centered world view. This usually involves some effort to come to terms with our roots plus the integration of new material such as political feminism, self-education in the realm of Jungian psychology, reclamation of lost history and mythologies, or the embrace of the practices and imagery of other cultures. There are as many different journeys as there are women taking them. I use the word “journey” because this is a process that is alive and evolving, and perhaps arriving at an answer is contrary to the nature of the quest.

One of the core problems is that there is a difference between an intellectual exploration of divinity and actual belief. It is the “believing” that is the tricky part, as it is soul work that takes its own time and can’t always be willed. We can inform ourselves about the mythologies of other cultures, but unless we are of those cultures it is difficult to arrive at an authentic relationship to them. This is imaginative work. In pursuing it we are trying to re-imagine our world as a place where women have dignity, where a woman’s integrity as an individual is not threatened, and where women are truly free to express themselves intellectually and spiritually. Part of the re-imagining may involve the trying on of different masks and even different rituals to see which ones will allow us to step into the sacred space we seek.

The root of imagine is “image”. Throughout time, images or ritual objects have helped people enter a spiritually receptive state of mind. For artists, it is fascinating to consider the role that such objects can play in facilitating the task of imagining and the step beyond imagining that is believing.

How can we invest an object with spiritual content or power when we are still feeling out our own spirituality? There are two ways in which an object may have spiritual content. One is the place it holds in the personal journey of the maker, and the other is the energy it carries for the beholder. When there is a consonance between the spiritual needs of the maker and the beholder, the object resonates.

I am not here addressing the issue of symbolism (as in the use of the cross to convey a whole set of ideas to the practicing Christian), but rather the qualities of intrinsic spiritual energy that a specific object may possess. It is in this arena that we must immediately begin to confront the issue of authenticity. No matter how skilled we are, the object we make will not resonate deeply if we are simply “trying on” a set of beliefs. The most powerful objects are those invested so truthfulIy with the beliefs of the maker that they reach across all barriers of time, space, and culture to touch the core of the beholder. The best have to do with the experience of being human in a universal and timeless sense.

There are built-in difficulties for the contemporary woman artist who is engaged in inventing her own spiritual journey from day to day and who wishes to reflect that journey in the objects she makes. The masks she tries on may help her grow, but do they reveal her true face? It is inherent in the process of invention that what fit us yesterday may no longer fit us tomorrow. How then to touch timelessness? In this culture of individuality, the irony is that the universal is probably most reachable when we have the courage to be honestly personal,

There is enormous risk of failure in this venture, failure to make work that resonates in the way we wish it would, failure to connect with anything but our own fantasies. Failure, however, is not the point. The point is having the courage to keep on trying. In conjunction with the spiritual struggle, which is always difficult, we must struggle with the constant temptations of a culture in which the marketplace is the sole determinant of value. I think it is no accident that women are at the forefront of the new spirituality, as it is mostly in our interest to buck the tide of commercialism since our sexuality has been most abused and compromised by market forces.

I am aware, however, that much of what I say applies to the creative process in general for men as well as for women. While it is true that women have struggles that are gender-specific, there is a healing that takes place in the period of withdrawal into one’s own gender. My hope is that part of that healing means arriving at a place where it is possible to recognize that men, too, are on a journey. In taking their hands as partners, we may eventually be able to envision and move toward a future that finds its center not in the spirit of one gender or the other, but rather in our common humanity.

P R O J E C T S

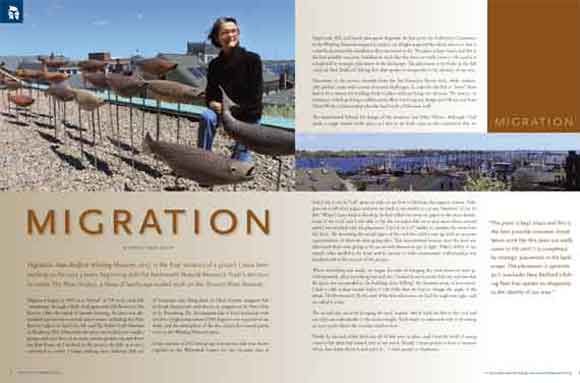

MIGRATION

published in The Bulletin of the New Bedford WHALING MUSEUM, summer 2013

by Nancy Train Smith

New Bedford Whaling Museum, 2013, is the final iteration of a project I have been working on for over 5 years, beginning with the Dartmouth Natural Resource Trust’s decision to create The River Project, a show of landscape scaled work on the Slocum River Reserve.

Migration began in 2009 as a “school” of 130 terra cotta fish “swimming” through a field of tall grass and wild flowers on the Reserve. After the initial 10 month showing, the piece was dismantled and moved to several other venues, including the Matt Burton Gallery in Surf City, NJ, and The Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton, MA. Ultimately, the piece was broken into smaller groups and now lives on in many private gardens up and down the East Coast. As I worked on the project, the fish, as it were, continued to evolve. I began making more elaborate fish out of stoneware clay, firing them in Chris Gustin’s anagama kiln in South Dartmouth, and also in an anagama at St. Pete’s Clay in St. Petersburg, FL. An anagama kiln is fired exclusively with wood to a high temperature (2300 degrees) over a period of one week, and the atmosphere of the fire creates the natural patina seen on the Whaling Museum piece.

In the summer of 2012 this group of stoneware fish were shown together at the Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in-Edgecomb, ME, and faced subsequent dispersal. At that point the Collection Committee at the Whaling Museum stepped in, and to my delight acquired the whole school so that it could be permanently installed as they are meant to be. The piece is kept intact and this is the best possible outcome. Installation work like this does not really come to life until it is completed by strategic placement in the landscape. The placement is symbolic as the fish overlook New Bedford’s fishing fleet that speaks so eloquently to the identity of our area.

Placement on the terrace viewable from the San Francisco Room deck, while aesthetically perfect, came with certain structural challenges. In order for the fish to “swim” there had to be a system for holding them in place without being too obvious. The system, or armature, ended up being a collaborative effort involving my design and Olivier and Sons Metal Works craftsmanship plus the hard work of Museum staff.

The mastermind behind the design of the armature was Mike Olivier. Although I had made a rough model of the piece as I saw it, we both came to the conclusion that we had to lay it out in “real” space in order to see how to fabricate the support system. Mike gave me a roll of tar paper, and sent me back to my studio to cut out “shadows” of the 34 fish. When I came back to his shop, he had rolled out more tar paper to the exact dimensions of the roof, and I was able to lay the tar paper fish on it and move them around until I was satisfied with the placement. I stood on a 15' ladder to simulate the view from the deck. By recreating the actual space of the roof we could come up with an accurate representation of what we were going after. This was essential because once the steel was fabricated there were going to be no second chances to get it right. Mike’s ability to see exactly what needed to be done and to execute it with consummate craftsmanship was fundamental in the success of the project.

When everything was ready, we began the task of bringing the steel pieces in and up. Unfortunately, after everything was laid out, I looked down from the balcony and saw that the piece was too parallel to the building, thus “killing” the dynamic sense of movement. I had to take a deep breath before I told Mike that we had to change the angle of the whole 750 lb structure! By the end of the first afternoon, we had the angle just right, and we called it a day.

The second day involved bringing the steel “staples” which hold the fish to the roof and cut each one individually to the correct height. Each staple is cushioned with vinyl tubing at every point where the ceramic touches steel.

Finally by the end of the third day all 34 fish were in place, and I had the thrill of seeing come to life what had existed only in my mind. Mostly, I want people to have a moment where they think about it and enjoy it... I want people to daydream.